Digital Privacy and the Charter: 2024 Year-in-Review

In 2024, the Supreme Court of Canada decided three cases related to digital privacy rights under the Charter. While there was a general trend toward broader protections for digital privacy rights, the Court was strongly divided on several key issues. Digital privacy continues to be a contentious issue, making it difficult to predict how the area will evolve in the years to come. In Bykovets, a 5-4 majority of the Court ruled that police need a warrant to request an IP address from a third party. In Campbell, the Court issued four different sets of reasons dealing with a police search of text messages. All nine judges purported to take a normative, content-neutral approach to their privacy analysis, but they ultimately reached different conclusions. And in York Region District Schoolboard, the Supreme Court offered obiter guidance on search and seizure in administrative contexts, providing an insight into one of the digital privacy issues which will continue to be litigated in the future.

1. R v Bykovets: Reasonable expectation of privacy in an IP address

R v Bykovets, 2024 SCC 6 was 2024’s most significant case for privacy rights under the Charter.

In Bykovets, a 5-4 majority of the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that there is a reasonable expectation privacy in an IP address, and therefore a request by the state for an IP address is a search under section 8 the Charter. Police now require prior judicial authorization to request an IP address from a third party.

However, Bykovets also included a strong dissent authored by Justice Côté. The Court was ultimately divided on just how far to stretch the “normative” approach to

Background: IP addresses, Internet Service Providers, and Police requests for subscriber information

You need an IP address to access the internet. It is a unique string of numbers that identifies the source of any online activity and connects that activity to a specific location.

Internet Service Providers (e.g., Bell or Rogers) assign an IP address to each of their subscribers. While the Internet Service Providers may change your IP address from time to time, they keep track of IP addresses assigned to each customer.

During a criminal investigation, police may observe illegal activity associated with a particular IP address. To link this IP address to an individual, police usually seek the help of Internet Service Providers because they hold the name, address, and contact info of the subscriber they assigned to the IP address at the material time. Police need judicial authorization before they can ask the Internet Service Provider to share that information (R v Spencer, 2014 SCC 43).

Facts of the case R v Bykovets dealt with an intermediate step in the investigative process described above.

In Bykovets, an anonymous person used stolen credit card data to make online purchases from a liquor store. Moneris, a third-party payment processor, managed the online store’s payments. Calgary Police contacted Moneris and requested the IP addresses associated with these fraudulent purchases. Moneris voluntarily provided two IP addresses.

Police then obtained a production order compelling the Internet Service Provider to disclose the names and addresses associated with the IP addresses. Mr. Bykovets was the registered owner of one of the IP addresses.

Reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses

In a split 5-4 decision, the majority ruled that Mr. Bykovets had a reasonable expectation of privacy in his IP address. The police request to Moneris for the IP address was therefore a search which required prior judicial authorization.

Writing for the majority, Justice Karakatsanis made the following points:

-

“Digital breadcrumbs”: An IP address can be the first “digital breadcrumb” leading police onto the trail of a person’s internet activity. An IP address can be correlated with a wide range of online activities, ultimately revealing a person’s entire online life. Recognizing a reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses will safeguard the first “digital breadcrumbs” and protect a person’s trail of internet activity from state intrusion. (Bykovets at paras 13, 69)

-

Normative approach to privacy: Courts must take a normative approach to privacy. When assessing reasonable expectations of privacy, the normative approach requires a broad, functional assessment of the subject matter of the search and its potential to reveal personal information. Here, the focus during the reasonable expectation of privacy analysis is on what information an IP address tends to reveal, and not on the specific purpose for which the police sought the IP address in this case.

-

Data in the hands of third parties: The internet has concentrated massive amounts of data into the hands of a few private third parties. These third parties are not subject to the Charter, but they now mediate the relationship between individuals and the state. Private parties can decide whether or not to reveal someone’s personal information to the state. By requiring prior judicial authorization for IP address requests, Bykovets brings the decision to reveal personal information to the state within the purview of the Charter.

Majority vs Dissent: Different views on the “subject matter” of the search

The key difference between the majority and dissent was in how they classified the subject matter of the search.

The majority classified the subject matter of the search as not only the IP address itself, but also the information that an IP address tends to reveal about a user. Writing for the dissent, Justice Côté classified the subject matter as the IP address and the identity of the Internet Service Provider associated with that IP address.

In Justice Côté’s opinion, the IP address on its own did not reveal the user’s identity or their internet activity. Because this personal information was not revealed by the "raw IP address” alone, it was not the subject matter of the search. This narrower classification of the subject matter led to the dissent finding that Mr. Bykovets did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in his IP address.

The Court here was divided on just how far the “normative approach” to privacy should be stretched. While all nine justices agreed that courts need to take a broad, purposive approach to classifying the subject matter of a search, their disagreement in the result shows that this is not a straightforward task in the digital era.

Future questions: publicly visible IP addresses and the use of peer-to-peer file sharing services

In concluding that there is a reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses, the majority hoped to protect the first “digital breadcrumbs” and “obscure the trail" of a person’s online activities. However, lower courts are now trying to figure out just how far this protection should extend. Does Bykovets establish a reasonable expectation in IP addresses regardless of the circumstances, or are there situations where it does not apply? One area of interest is the use of peer-to-peer file-sharing services like BitTorrent.

In Bykovets, the Court was dealing with a situation where police requested the IP address from a third party. However, peer-to-peer networks do not rely on centralized third parties. Users share files directly with one another, and as a result the users can see each other’s IP addresses.

In R v Currie, 2024 BCPC 175, police used an automated tool to monitor peer-to-peer network activity and identified an IP address that was sharing child sexual abuse material. The trial judge noted that, given the fact that users of peer-to-peer networks can see each other’s IP addresses, it was hard to see how the accused would have a reasonable expectation of privacy in his IP address. Nonetheless, the trial judge felt that Bykovets established a blanket reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses, regardless of the circumstances. The judge concluded that police needed prior judicial authorization to monitor the file sharing service, even though IP addresses were publicly visible to all users.

A narrower reading of Bykovets would suggest that it does not apply here, because there was no police request to a third party. However, given the majority’s broad and sweeping approach to online privacy, we may see lower courts struggle to figure out with where Bykovets does and does not apply.

2. R v Campbell: Reasonable expectation of privacy in text messages, and “interceptions” using new technologies

In R v Campbell, 2024 SCC 42, the Supreme Court revisited reasonable expectations of privacy in text messages, and also considered the meaning of an “interception” under Part VI of the Criminal Code.

As in Bykovets, the Court was divided here. While the judges reached a near-consensus on the normative, content-neutral approach to reasonable expectations of privacy, they disagreed on how to define an “interception” in light of 50 years of technological advancements (Parliament enacted Part VI of the Criminal Code in 1974).

Facts of the case

Police arrested Kyle Gammie and lawfully seized his phone. Minutes later, someone named “Dew” texted Mr. Gammie’s phone and offered to sell him drugs. The messages appeared on the lock screen and police viewed them without unlocking the phone.

Based on the contents of these initial messages, police believed that the dealer would soon sell the drugs elsewhere if they did not apprehend him. Police replied to the texts from the lock screen without unlocking the phone. They impersonated Mr. Gammie and arranged a drug deal with Dew. Police then met up with the appellant, Dwayne Campbell, and arrested him. They charged him with trafficking and possession offences under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA).

Campbell testified that he was not “Dew”. Rather, someone else named Dew sent the initial text messages, then gave Campbell the phone and asked him to deliver the drugs. According to Campbell, it was not his phone, and he only sent the subsequent texts after police began impersonating Gammie.

Multiple issues relating to the search

The text messages at issue in this case were the ones sent to police after they began impersonating Gammie to set up the drug deal. Campbell sought to have these text messages excluded.

The Supreme Court had to decide a number of issues in this case: Did Campbell have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the text message conversation?

Did police conduct an unreasonable search?

- Was the search an “interception” under Part VI of the Criminal Code?

- Was the search incident to arrest?

- Was the search authorized by section 11(7) of the CDSA because there were exigent circumstances which made it impracticable to obtain a warrant?

If police violated Campbell’s section 8 rights, should the Court exclude the evidence under section 24(2) of the Charter?

The issues that this blog post will explore in more detail are 1. whether Campbell had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the text message conversation, and 2a. whether the police conduct amounted to an “interception” under Part VI of the Criminal Code.

Breakdown of the four sets of reasons

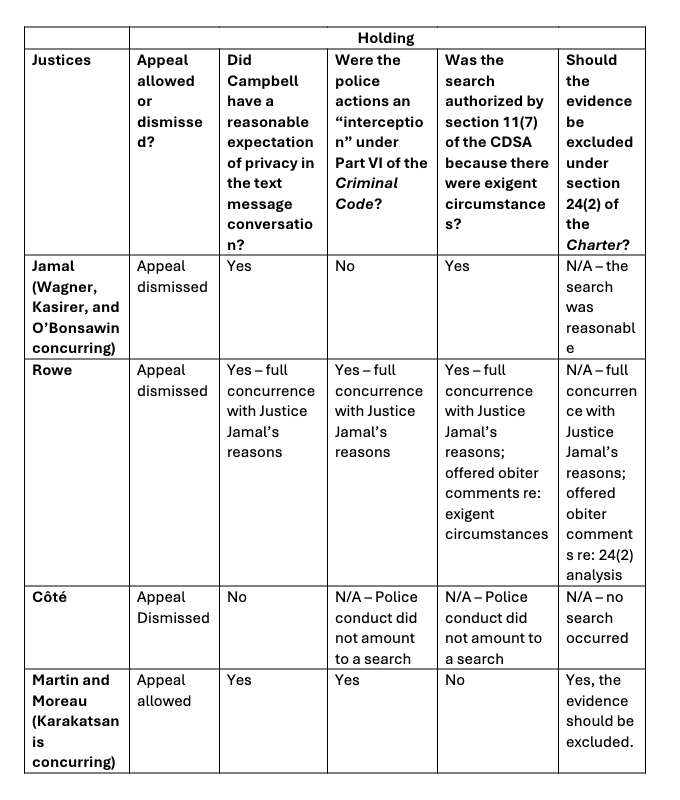

The Supreme Court was fragmented in Campbell, issuing four separate sets of reasons. Six judges dismissed the appeal, finding that there was no violation of section 8. The 4-1-1-3 split in this decision and the 5-4 split in Bykovets should serve as an indication of how the difficult nature of digital privacy issues.

Campbell had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the text messages

Eight of the nine judges agreed that Campbell had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the text messages he sent, and that the police conduct amounted to a warrantless search of these text messages. Justice Côté was the only judge who found that the text messages did not attract a reasonable expectation of privacy, and that no search occurred.

Justice Jamal used this case as an opportunity to affirm the basic principles of the normative, content-neutral approach that courts should take when assessing expectations of privacy.

The normative approach requires courts to look at whether the subject matter of the search has the potential to reveal personal information. Content-neutrality means that the determination of whether a reasonable expectation of privacy exists does not turn on whether the items that the police were seeking were in fact illegal. Here, the contents of the text messages were not important. What mattered was the potential for text messages, generally, to reveal private information.

With a normative approach to privacy, courts are in a position to make value judgments about what privacy protections ought to look like in Canadian society. However, critics of this approach might say that there is a risk of the reasonable expectation of privacy analysis becoming divorced from the actual facts of the case. This was Justice Côté’s view in her concurring reasons.

According to Justice Côté, the factual context of each case should play a more central role in the reasonable expectation of privacy analysis. An over-emphasis on the subject matter’s potential to reveal personal information could lead to a blanket finding that all text messages attract a reasonable expectation of privacy, regardless of the circumstances. This would run contrary to the idea that courts should assess expectations of privacy in the “totality of the circumstances”.

The police conduct was not an “interception”

While there was a near-consensus on the reasonable expectation of privacy analysis, the Court was more divided on the issue of whether police had conducted an “interception” of Campbell’s private communications. The broad, functional approach taken in the reasonable expectation of privacy analysis stands in contrast to the narrower interpretation of the words “interception” and “device” by the majority.

Part VI of the Criminal Code defines “interception” and makes it an offence to intercept private communications by use of “any electro-magnetic, acoustic, mechanical or other device” without judicial authorization. The requirements for authorizing an interception are more stringent than for other types of search warrants, reflecting the intrusiveness of an interception and the heighted privacy interests at play.

Justice Jamal (with Wagner, Kasirer, O’Bonsawin, and Rowe concurring on this point) found that the police actions were not an interception because they did not employ an “intrusive surveillance technology”. Jamal said that “deception is not interception” unless it also involves the use an intrusive technology. He emphasized another section of Part VI, which says that interception warrants include the ability to “install, maintain or remove the device covertly.” This, Justice Jamal said, implies that an interception device must be distinct from the medium of communication it is being used to intercept.

Justices Martin and Moreau in dissent (with Karakatsanis concurring) reasoned that an interception did not require the use of a separate device. Here, Gammie’s cellphone was a “device” that police used to intercept private communications from Campbell. Martin and Moreau took a normative, technologically-neutral approach, saying that because a text message exchange creates a record of the communication in writing, it is analogous to other types of interceptions such as police recording a phone call.

3. York Region District School Board v Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario: Guidance on s. 8 privacy in administrative contexts

York Region District School Board v Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2024 SCC 22 involved multiple digital searches in the workplace. The case involved both administrative law and search & seizure issues.

The Supreme Court decided this case on the basis of the administrative law issues and did not need to determine whether or not the searches were constitutional. However, the majority chose to provide guidance in obiter about section 8 privacy rights in administrative contexts. With the division of the Court in Bykovets and Campbell, the application of section 8 in administrative contexts is an area to watch over the next few years. The Supreme Court’s broad, purposive approach to privacy has come primarily in the criminal context, while the Court in York Region District School Board emphasized that expectations of privacy can be diminished in non-criminal settings.

Facts of the case

Two teachers created a shared Google Doc which they used to document instances of workplace bullying. The document was stored in the cloud and was only accessible using the teachers’ personal Google accounts. However, the teachers accessed the Google Doc using devices owned by the school board.

One of the teachers left the Google Doc open on a school computer and went home for the evening. The school principal found the document open and unlocked on the classroom computer. He read what was visible, then scrolled through the document and took photos of it. The school board reprimanded the two teachers based on what they wrote in the document.

The teachers’ union filed a grievance, claiming that the school board violated the teachers’ privacy rights.

Case history

A labour arbitrator found no privacy violations. The arbitrator did not consider the Charter.

On appeal, the Divisional Court ruled that the Charter did not apply to the school board. The Divisional Court found no errors with the arbitrator’s decision.

The Ontario Court of Appeal, however, disagreed. The Court of Appeal found that the Charter did apply to the school board. Considering the totality of the circumstances, the Court of Appeal ruled that the teachers had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the Google Doc and that the school principal conducted an unreasonable search under section 8 of the Charter.

Reasonable expectation of privacy in the Google Doc

The Court of Appeal emphasized certain facts which tended to support a reasonable expectation of privacy, while seemingly minimizing the facts which would not. The Court said that the teachers did all they could to protect their privacy by using personal Google accounts and not sharing the document with others. On the other hand, the Court considered the fact that the teacher left the document open in plain view to be a “careless oversight”, and not something that should diminish privacy. The use of a school computer rather than a personal device also did not diminish the expectation of privacy in the Google Doc.

The facts of this case certainly suggest that the teachers had a subjective expectation of privacy in the document, but it is less clear whether that expectation was reasonable in the totality of the circumstances.

Supreme Court provides guidance in obiter

It would have been interesting to see the Supreme Court analyze the facts of this case and determine whether there was a reasonable expectation of privacy in the totality of the circumstances. Instead, they disposed of the case without needing to go through a full section 8 analysis. The Court’s finding that the Charter applied to the school board was dispositive.

However, because the Court of Appeal dealt with section 8 and the parties before the Supreme Court made extensive submissions on the section 8 issues, the Majority felt the need to provide guidance on section 8 in obiter. They made the following points about how courts should analyze section 8 privacy rights in administrative contexts:

- The role of criminal law: Criminal decisions can assist in determining the existence and scope of reasonable expectations of privacy in the workplace. For example, criminal cases involving searches in schools may assist with assessing reasonable expectations of privacy for teachers. However, criminal law principles should not be indiscriminately applied to non-criminal cases. Section 8 involves the balancing of an accused person’s privacy interests against other societal interests which are advanced by the state’s privacy intrusions. Where the stakes are higher for an accused person, this will necessarily affect this balancing exercise.

- Reasonable searches in non-criminal contexts: Some searches which would be unreasonable in a criminal context could be still reasonable in non-criminal settings. For example, the stakes are lower in labour relations than they are in criminal proceedings, and this is important context for assessing the reasonableness of the search. In the labour context, the terms of a collective agreement can inform the reasonableness analysis.

- Operational realities, policies, and procedures: Reasonable expectations of privacy are assessed in “the totality of the circumstances”. In the workplace, an employee’s reasonable expectations of privacy will be coloured by their employer’s operational realities, policies, and procedures. For example, a policy stating that data stored on work devices is owned by the employer would reduce expectations of privacy in that data.

Conclusion

In 2024, the Supreme Court strengthened digital privacy protections under the Charter by recognizing a reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses and reiterating the key underlying principles of a normative and content-neutral approach to privacy The Court also confirmed that the Charter applies to public school boards and offered guidance on how the section 8 analysis differs in administrative contexts

There was a general trend toward broader digital privacy protections in 2024. However, the Court was divided in its digital privacy analysis, making it difficult to predict how privacy rights will evolve in 2025 and beyond.

The opinion is the author's, and does not necessarily reflect CIPPIC's policy position.